Oct 09, 2025·7 min read

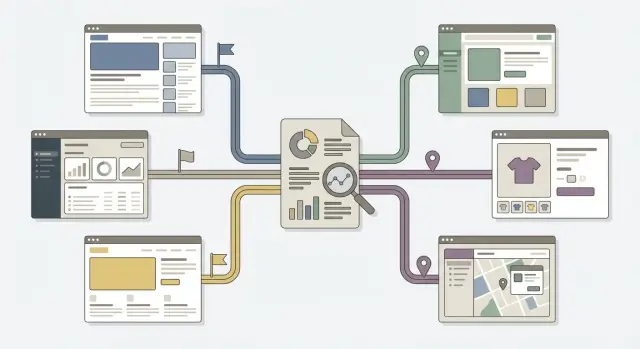

Scale content across multiple websites without duplicate pages

Learn how to scale content across multiple websites by reusing research, localizing thoughtfully, and keeping every page unique and useful.

Why scaling content often turns into duplicate pages

When teams try to scale content across multiple websites, the fastest move is copy, paste, then tweak a few words. It feels efficient, but it usually backfires. Search engines and readers spot sameness quickly, even when the wording changes.

The biggest confusion is mixing up reused research with duplicated content.

Reused research is the shared foundation: stats, definitions, common questions, and basic facts.

Duplicated content is when the page is basically the same page: same structure, same points in the same order, same examples, and the same ending.

"Unique, helpful" doesn't mean inventing new facts for every site. It means the page earns its space by fitting a specific audience and context. A reader should feel, "This was written for my situation," not "I've seen this exact page somewhere else."

Scaled pages usually start to look duplicated when you reuse the same headline, reuse the same section order, keep the same examples, and only swap a few keywords (like city names). Repeating the same CTA and next-step guidance across every site also makes pages feel cloned.

Consistency is good. Keep your core facts aligned, use the same terms for the same concepts, and maintain a recognizable voice. Sameness is the problem: identical logic, identical proof, identical takeaways.

A quick example: imagine you publish "email deliverability tips" on three sites: a startup blog, an agency site, and a help center. The research can be the same (common causes of spam, authentication basics). But each page should change what it emphasizes, the problems it solves, and the examples it uses. The startup version can focus on first campaigns. The agency version can focus on reporting to clients. The help center can focus on step-by-step fixes.

What you can reuse safely (and what you should rewrite)

When you scale content across multiple websites, the safest thing to reuse is the research, not the writing. Think of research as ingredients, and each page as a different meal.

Research you can reuse without creating "same page, different logo": facts and definitions, stats and data points (with source notes and dates), real customer questions, key steps or criteria, and your source notes (quotes, study titles, and other references stored in your research pack).

What usually causes duplicates is the wrapper text. Even when the facts stay the same, write these fresh for each site:

- Intros and hooks that match that site's audience and tone

- Examples and scenarios that fit different roles or industries

- Comparisons and alternatives (what people compare against changes by site)

- Conclusions and calls to action with a clear, relevant next step

A practical way to keep one source of truth without reusing sentences is to store bullet facts, not finished paragraphs. For example, your research pack can say: "Benefits: saves time on drafting, improves consistency, reduces missed topics." Each site can then choose its own wording, order, and emphasis.

Also validate research region-by-region when it can change. Laws, pricing, tax rules, medical claims, units (miles vs km), spelling (US vs UK), and even local expectations (shipping times, payment methods) can make a copied page inaccurate.

Build a research pack that scales

A research pack is the shared source of truth you reuse when publishing across multiple websites. It holds facts and raw material, not final wording, so each site can write a unique page without starting from zero.

Think of it as a folder (or doc) that answers: what do we know, what do we need to prove, and what questions will readers ask?

A strong pack usually includes:

- Key points and the single takeaway you want readers to remember

- Evidence (stats, studies, quotes) with where you found them and the date

- A mini glossary of terms that must stay consistent

- Common objections and clear, plain-language responses

- A handful of examples you can adapt per site or audience

Add a short "reader intent" note at the top: what problem the page solves, who it's for, and what a good outcome looks like. This stops teams from filling space with generic content.

To prevent drift, use a simple naming and versioning system. One format that works: TopicSlug - Audience - Region - v1.0. Update versions only when the facts or positioning change, and log changes in a few bullets (what changed and why).

Finally, include a "localization notes" block: what must change by site or region (units and currencies, legal claims, locally relevant examples, and the terms people actually search for).

Choose a unique angle for each website or section

To scale content across multiple websites without cloning pages, decide the angle before you write. The same topic can serve different readers, but only if you're clear about who the page is for and what they want to accomplish.

Start by naming the audience for each site or section. Are they beginners who need definitions and safety checks, or experienced buyers who want numbers, comparisons, and gotchas? Also note what they already know. A niche site can skip basics that a general site must explain.

Next, be honest about what each site can credibly claim and show. If one site has real experience (projects shipped, results measured, edge cases handled), it can lead with proof and lessons. If another site is broader, it can lead with a clear overview and a simple decision guide. Credibility is part of what makes a page feel unique.

A quick way to lock the angle:

- Who is this page for (role, situation, urgency)?

- What do they care about most (cost, risk, speed, quality)?

- What can this site prove (examples, data, firsthand tips)?

- What will this page cover that others won't (specific use cases or problems)?

Then plan different supporting sections per site. One page might add FAQs for first-time readers. Another might add troubleshooting for people who already tried and failed. A third could add a simple comparison table of approaches.

One-sentence test: "This page is worth reading because it helps [audience] do [specific outcome] with [this site's specific focus or proof]."

Localization that actually changes the page

Render content in Next.js

Use ready-made npm libraries to display GENERATED content on your site.

Translation is the easy part. Real localization changes what the page does for a reader in that place: it answers their common questions, uses familiar terms, and removes little bits of friction that make people leave.

Start with language choices that sound normal locally: spelling (optimize vs optimise), tone (more direct vs more formal), and reading level. Even small phrasing choices matter. "Support team" may feel natural in one region, while "customer service" is the default in another.

Then adapt the practical details people scan for before they trust you. These edits also help prevent "same page, different language" duplication:

- Currency, taxes, and billing wording (USD vs GBP, VAT invoices where expected)

- Units, dates, and time conventions (mm/dd/yyyy vs dd/mm/yyyy, meters vs feet)

- Logistics and service details (shipping expectations, return windows, support hours and time zones)

- Region-specific trust signals (privacy wording, warranties, common payment methods, industry standards)

- Examples that feel native (local industries, seasons, everyday references)

Keep a global core when the facts are universal: definitions, capabilities, and the high-level process. Fully rewrite when intent differs by locale. For example, a page about API-delivered blog content can keep the same "how it works" section, but pricing expectations, compliance concerns, and proof points often need a rewrite.

A practical approach: keep one shared research pack, but localize the top of the page (headline, intro, objections, examples) and the bottom (FAQ, trust, checkout details). Those sections decide whether the page feels made for that reader.

A step-by-step workflow to scale without cloning

The safest starting point is shared research, not a copied draft. Treat every new page as a fresh build that happens to use the same source notes.

The workflow

-

Start with your research pack (sources, key facts, stats, definitions, quotes, objections). Don't open an old published page first. That stops you from inheriting its structure and phrasing.

-

Write a 3-line brief for the specific site or section: who the reader is, what single problem they have, and what you want them to do after reading. If you can't write this in three lines, the page will drift.

-

Draft a new outline from scratch. Reuse the facts, but change the order, headings, and emphasis to match that brief. Two sites can share the same data but tell different stories.

-

Write a fresh intro, examples, and recommendations that fit the site's context. A B2B site can open with a team workflow problem. A consumer site can open with a budget or time-saving scenario.

-

Localize with real changes: units, currency, spelling, legal or cultural notes, and region-specific FAQs. Then scan for mismatches (wrong currency, holiday timing, local terms that don't exist in that region).

-

Do a final usefulness check. Read it as the target reader and ask: would this page still help if the other site's version didn't exist? If not, tighten the goal, add one more site-specific example, and remove generic filler.

Templates that don't produce identical pages

Templates are useful, but reusable paragraphs are risky. If the same wording shows up across sites, pages start to feel copied, even when the topic is valid. The safer approach is to reuse structure, not sentences.

Build pages from roles, not paragraphs

Think in content blocks that answer different reader needs. The template stays the same, but the writing inside each block is created for that site's audience.

A simple block set that stays useful without turning into duplicates:

- Definition: explain the concept using terms your audience actually uses

- Steps: a short sequence that matches how your readers work

- Pitfalls: the top 2-3 mistakes most common for that site

- FAQ: questions pulled from that site's search intent

- Proof: one specific example, metric, or mini case that fits the audience

After the structure, vary the proof and scenarios on purpose. If one site uses a B2B story, another can use a local service story, and a third can use an ecommerce scenario. Even small changes help: different constraints, different tools, different outcomes.

Comparisons and alternatives should shift too. A marketing team might search "best option," while a newsroom might search "editorial workflow." Match what they compare against, and the page becomes naturally unique.

Keep terminology consistent (per site)

Uniqueness shouldn't mean chaos. Each site needs one set of preferred terms, even if another site uses different ones.

Create a short style checklist per site: voice and point of view (we/you), formatting rules (heading style, paragraph length, list size), allowed claims (what you can promise vs what needs evidence), and preferred terms (plus a short "do not use" list).

Quick checklist before you publish

Refresh content without rework

Update pages when research changes and republish cleanly across sites.

Before you hit publish, do one last pass as if you landed on this page from search and have only a few seconds to decide if it helps. If the first screen feels vague or like it could belong on any site, pause and tighten it.

- First 10 seconds: Does the opening answer a real question quickly (what it is, who it's for, what you'll get)? If you can't summarize the benefit in one sentence, the intro is too fuzzy.

- Site specifics: Are the examples and terms clearly tied to this audience? One familiar industry detail can make the page feel original.

- Structure: Does the page have its own shape, not the same headings in the same order as your other versions?

- Locale accuracy: Are prices, units, taxes, regulations, and claims correct for the region?

- Next step: After reading, is the action obvious and relevant to this site?

A concrete test: imagine someone reading on a phone while deciding between two options. If they can't find a clear answer and a clear action quickly, the page will struggle even if it's technically "unique."

Common mistakes that create thin or duplicate content

Most duplicate content problems aren't caused by copying an entire page. They come from repeating the same skeleton while changing a few surface details.

One common trap is localization that only swaps city names, currencies, or a couple of phrases. Readers can tell when the page is the same advice with a different place label. Real localization changes examples, constraints, and priorities. A London page might mention commuting costs and dense neighborhoods, while a Phoenix page might focus on heat and driving distances.

Another mistake is reusing the same intro and conclusion on every site. Even if the middle differs, repeated openings and closings create a strong duplicate signal and make the brand feel generic.

Many teams try to fix repetition by swapping in synonyms. That often makes the text longer without making it more useful. Thin content isn't about word count. It's about missing specifics: steps, examples, limits, pricing context, or what to do next.

Copying quickly also breaks internal consistency. A page might use the wrong feature name, outdated offer terms, or a support policy that belongs to another site. That hurts trust more than any SEO issue.

Red flags to watch for:

- Only the location names changed, but the advice and examples stayed the same

- The first and last paragraphs match across sites

- Lots of rewording, little new information

- Mixed terminology for the same concept

- Content ships faster than anyone can review or update facts

A practical safeguard is to keep a "facts and terms" sheet per site and require a quick review before publishing.

Example: reusing one research pack across three sites

Turn briefs into new outlines

Generate fresh structures and angles so each site gets its own page shape.

Imagine you have one strong research pack on "how to choose a project management tool": clear definitions, a short comparison table, common pitfalls, and a simple evaluation checklist. Now you need three pages that share the backbone without looking like copies.

Here's how the angle can change while the research stays consistent:

- Brand site: Focus on decision confidence. Use headings like "Questions to ask in a demo." Examples reference cross-team work (marketing + ops). FAQs focus on buying concerns like onboarding time, security, and pricing terms.

- Niche site (freelancers): Focus on working solo. Examples cover client approvals, time tracking, and avoiding features you won't use.

- Regional site: Focus on local context. Examples and FAQs cover local compliance, support hours, language expectations, and common payment options.

What stays consistent across all three pages: the core definition, the same key steps for evaluation, and the same evidence-based claims (with the same sources in your internal notes).

Before vs after: the "before" version reused the same intro, feature list, and FAQ with only the site name swapped. The "after" version keeps one research backbone but gives each page distinct headings, examples, FAQs, and next steps.

Next steps: build a repeatable pipeline for scale

Scaling content across multiple websites works best when you treat it like product work: small cycles, clear ownership, and measured outcomes. The goal isn't publishing faster at any cost. It's keeping each site genuinely useful and distinct while still reusing the same research.

Set a refresh cadence for your research packs. Low-risk topics (basic definitions, stable how-tos) can be checked quarterly. Higher-risk topics (pricing, laws, fast-changing trends) should be reviewed monthly. Outdated "shared facts" quickly turn into shared mistakes.

Keep performance tracking separate by site. A page can rank on one site and flop on another because the audience, intent, and internal navigation differ. Track two simple signals per site: which search questions bring clicks, and where readers drop off (often a section that feels generic or off-target).

A change log keeps updates consistent without copying text. Log what changed in the research pack, what must change everywhere (facts, numbers), and what must stay site-specific (examples, phrasing, recommendations).

If you want to automate parts of the pipeline without defaulting to clones, GENERATED (generated.app) is designed to generate content from shared research, support translations, and produce site-specific CTAs with performance tracking, while still letting each page keep its own angle and examples.

FAQ

What’s the safest way to scale content across multiple sites without creating duplicates?

Reuse the research, not the finished paragraphs. Keep one shared set of facts, definitions, and source notes, then write a new outline, intro, examples, and next step for each site so the page fits a specific audience and context.

What’s the difference between reused research and duplicated content?

Reused research is shared raw material like stats, definitions, and common questions. Duplicate content is when the page is essentially the same page again, with the same structure, points in the same order, similar examples, and the same takeaway, even if the wording is lightly changed.

Why does “copy, paste, tweak” usually backfire?

Search engines and readers are good at spotting sameness in structure and intent, not just exact wording. If multiple pages follow the same logic, use the same proof, and end with the same advice, they feel cloned and are less likely to stand out or earn trust.

What parts can I reuse safely, and what should I rewrite every time?

Reuse facts and definitions, stable criteria or steps, and your internal source notes with dates. Rewrite the hook, section order, examples, comparisons, objections, and the conclusion so each page reflects what that site’s readers actually care about.

How do I keep a “single source of truth” without reusing the same sentences?

Store bullet-point facts, evidence notes, and questions instead of finished prose. When writers pull from bullets, they naturally change wording, emphasis, and order while still staying accurate and consistent.

What should a good research pack include?

Include the key takeaway, evidence with where it came from and when, a mini glossary of must-use terms, objections with plain responses, and adaptable examples. Add a short intent note at the top that says who the reader is, what problem they have, and what success looks like.

How do I pick a unique angle for each website so pages don’t feel cloned?

Give each page a clear angle before writing: who it’s for, what outcome they want, what they care about most, and what this site can credibly show. Then build a fresh outline that supports that angle, even if the underlying research is the same.

What’s the difference between translation and real localization?

Translation changes words; localization changes usefulness. Update currency, units, dates, taxes, compliance wording, support expectations, and examples that feel normal in that region so the page reads like it was made for that place, not simply converted.

What’s a simple workflow to produce unique pages at scale?

Start from the research pack, write a three-line brief for that site, draft a new outline from scratch, then write fresh intros, examples, and recommendations. Do a final usefulness check by asking whether the page would still help if the other site’s version didn’t exist.

What are the most common mistakes that create thin or duplicate content?

Reusing the same intro and conclusion everywhere, keeping identical headings in the same order, and doing “localization” that only swaps city names or currencies. Another common issue is synonym-swapping that makes text longer but not more specific, which still feels thin and generic.