Nov 25, 2025·8 min read

Programmatic SEO for long-tail keywords: planning templates

Programmatic SEO for long-tail keywords: plan glossary, location, and comparison templates with quality checklists that prevent thin pages.

What you are trying to solve (and why thin content happens)

Programmatic SEO lets you create many search-friendly pages from one repeatable template, using keywords plus structured data. Instead of writing every page from scratch, you build a page pattern that can be filled with different terms, places, products, or attributes.

It works best for long-tail searches because people ask specific questions. One well-designed template can satisfy thousands of those queries - as long as each page is built around the searcher’s intent, not just a swapped keyword.

Thin content shows up when pages look different but say the same thing. That usually happens when:

- the data is missing, so the page falls back to vague filler

- the same paragraphs get reused everywhere

- you generate pages for keywords where there’s nothing unique to add

Search engines treat these pages as low value, and people bounce because they don’t get a real answer.

A fast fit check: can you provide unique inputs per page, not just a unique title?

If you can reliably add 3 to 5 specific facts (definitions, specs, prices, FAQs, pros/cons, local details), write a clear primary answer that truly changes by page, and skip generation when data is missing, you’re in a much safer zone.

Example: a “compare A vs B” template only works if you have real differences to show. If every page ends up saying “Both are popular options,” it’s thin - even if you publish 1,000 versions.

Choosing long-tail keywords that work with templates

Good programmatic SEO starts with real questions, not a spreadsheet of search volumes. Look for phrases where the searcher clearly wants one kind of answer: a definition, a local option, a price range, or a direct comparison. When intent is clear, a template can deliver a consistent, helpful page.

To find these, use language you already have:

- Google Search Console queries

- your site search

- customer emails and support tickets

- sales calls and chat logs

People describe the same need in different words. Those variations can map cleanly to one template, as long as the page is doing the same job.

Group by intent first, then by pattern

Group keywords by what the person is trying to do, not just by matching words. “What is X” and “X definition” belong together. “X vs Y” and “difference between X and Y” belong together too, but they need a different layout.

A few patterns that tend to template well:

- Definition intent: “what is [term]”, “[term] meaning”

- Location intent: “[service] in [city]”, “[service] near me”

- Comparison intent: “[tool] vs [tool]”, “[tool] alternatives”

- Pricing intent: “[product] pricing”, “cost of [service]”

- How-to intent: “how to [task]”, “best way to [task]”

Just as important: decide what you will not build. If you can’t add unique details per page, a template will create bloat.

For example, “best coffee shops in [tiny neighborhood]” might look templatable, but without real shop data and reviews, every page reads the same. This is where good guardrails matter: only generate pages when you can supply facts, examples, or steps that actually change with each query.

Picking the right template type: glossary, location, comparison

Pick your template based on intent, not on what’s easiest to publish. Templates work when many queries share the same core questions, but require different specifics.

Glossary pages (when people want clarity)

Use a glossary template when someone is trying to understand a term, acronym, metric, or method. A useful glossary page does more than define a word. It explains why it matters, where you’ll see it, and how it relates to nearby concepts.

Example: someone searching “what is customer churn rate” wants a plain definition, a simple formula, and a short example. They’ll also benefit from related terms (like retention rate and cohort analysis) and a quick list of common mistakes.

Location pages (when people want a local option)

Use location pages when the query implies a place and a service, like “accountant in Austin” or “same-day flower delivery Brooklyn.” These pages fail when you copy the same text and swap the city name.

A location page earns its place by including details that change by location: service coverage boundaries, local availability, pricing ranges if they differ, local proof (reviews, case studies), and location-specific FAQs.

Comparison pages (when people want to choose)

Use comparison pages when the query includes “vs,” “alternative,” or “best for.” These pages should help someone decide, not just list features. Focus on who each option is for, the tradeoffs, setup effort, and a clear recommendation based on scenarios.

Rule of thumb:

- Glossary: “What is X?” and “X meaning”

- Location: “X near me” and “X in [city]”

- Comparison: “X vs Y” and “best X for [use case]”

- If each page needs unique research, write a normal article instead

If the only unique input is the keyword, the page will read thin no matter how polished the writing is.

Step-by-step: planning one template from query to page

Start with one real query, not a template idea. Pick something specific like “best time tracking app for freelancers” or “plumber in Austin open Sunday.” Your job is to turn that intent into a page that answers quickly, then earns trust with detail.

Write the page goal as one measurable sentence. Example: “Help a visitor compare options in under 2 minutes and choose one next step.” If you can’t state the goal plainly, the template usually turns into filler.

Next, list the fields that must be different on every page to make it genuinely useful. Think beyond swapping a city name. For a comparison page, “pricing model,” “top 3 pros/cons,” “who it’s best for,” and “key limitations” are stronger than generic paragraphs.

A simple planning worksheet

Use this checklist while you sketch the layout:

- Define the one action the page should help with (choose, learn, contact, estimate).

- List the variable data you need per page (facts, numbers, attributes, quotes, hours).

- Mark each section as fixed (always present), flexible (changes size), or optional (only shows when data exists).

- Match headings to intent: what the searcher wants first, second, and third.

- Set a minimum publish bar: if required data is missing, don’t generate the page.

Headings should follow the question in the query. If the query is “X in Y,” the first heading should confirm relevance (“X in Y”), and the next headings should remove doubt (“Prices,” “Availability,” “What’s included,” “Alternatives”). Don’t add headings just to pad word count.

Define the minimum content bar in concrete terms. Example: “At least 3 unique facts, 1 locally relevant detail, 1 clear recommendation or next step, and no empty sections.” That bar is the difference between scaling value and scaling thin content.

If you generate pages via an API, treat missing data as a blocker, not a reason to publish a shorter page. Optional sections should disappear cleanly, not show placeholders.

What makes a templated page feel useful, not thin

A templated page stops feeling thin when it offers something you can’t get from one generic paragraph with a swapped keyword. If someone lands on the page first, they should leave with an answer and a next step - not the feeling they hit a placeholder.

The biggest upgrade is page-level differences that are real, not cosmetic. That means unique facts, clear constraints, and specific examples that match the query.

Add information that changes from page to page

Think in terms of “fields” that vary and matter.

A glossary entry can start with a plain definition, but it becomes useful when it explains when the term applies, what people confuse it with, and a quick real-world example.

A location page shouldn’t repeat the same pitch with a different city name. People want specifics: service boundaries, local considerations (delivery times, permits, seasonality), and what to do if they’re just outside the area.

A comparison page earns its spot by answering the next natural question: “Which one should I pick for my situation?” That requires scenarios, tradeoffs, and who each option is not for.

A few signals you’re building a stand-alone page (not a thin clone):

- one or two details only true for that page (numbers, rules, availability, examples)

- a short “common pitfall” that matches the query intent

- a mini decision rule (if X, choose Y)

- FAQs that change based on template data (not copied verbatim)

- a next action that fits the page (check eligibility, compare features, request a quote)

Avoid boilerplate intros and repeated paragraphs that look identical across hundreds of pages.

Quality checklist for each template (copy and reuse)

Plan unique fields in minutes

Use idea generation to define unique fields and sections before you build the template.

A template isn’t a shortcut to publish more pages. It’s a way to publish more useful pages that each answer one specific long-tail question.

Start with shared checks that apply to every page type, then add a few template-specific checks.

Shared checklist (every templated page)

- Write a unique, specific H1 that matches intent (not just a keyword swap).

- Use 2 to 4 helpful subheadings that guide scanning.

- Add a short summary near the top that reflects the page data, not generic filler.

- Provide one clear next step with no distracting blocks.

- Remove filler sections that repeat across all pages (generic benefits, copy-pasted FAQs).

Template-specific checks

- Glossary pages: define the term in plain language, add context (where you’ll see it), give a short example, and include 3 to 5 related terms that genuinely help.

- Location pages: be specific about what’s offered in that area, note boundaries or exceptions, add proof points that can vary, and include FAQs that reflect local concerns.

- Comparison pages: use clear decision criteria (price, features, ease of use, support), explain who each option fits, be honest about tradeoffs, and name realistic alternatives.

A quick test for thinness: if you remove the city name or term and the page still reads the same, it’s not unique enough yet.

Data sourcing and guardrails for consistent pages

Templated pages fail when the layout is fine but the inputs are messy. Treat your data like you treat copy: decide where each fact comes from, who owns it, and what happens when it’s missing.

Map every page field to a source. That includes obvious items (name, definition, address) and small ones (pricing range, last updated date, pros and cons). If you can’t name a source, that field shouldn’t ship.

A simple field dictionary is usually enough:

- Field name and plain-language description

- Source of truth (internal dataset, research notes, product info, manual review)

- Format rules (units, rounding, allowed ranges, tone)

- Refresh schedule (monthly, quarterly, on change)

- Owner (who fixes it when it breaks)

Then add guardrails that stop broken or misleading pages from being published. Allowed values matter: one unexpected value (like a blank city or malformed price) can produce dozens of bad URLs.

When data is missing, don’t fill space with fluff. Hide the section if it would be empty, or show a short note that helps the reader take the next step. Example: if a location page is missing opening hours, you can say “Hours vary by provider. Call ahead before visiting,” then still offer directions, nearby alternatives, and common questions.

Be extra careful with trust-sensitive claims. Numbers, rankings, “best” language, and legal or health-related statements should require approval before going live. Also keep a change log so template updates don’t quietly rewrite older pages in ways that change meaning or break formatting.

Common mistakes that create thin or duplicate content

Render content in Next.js

Render generated content with npm libraries for Next.js and other frameworks.

Thin pages usually happen when you scale before you know what “good” looks like. The risky part isn’t the template itself. It’s pushing thousands of pages live before one has proven it can rank, earn clicks, and satisfy the query.

Common failure modes:

- Launching at full volume on day one without validating intent and user behavior.

- Reusing the same opening paragraph, “what is” block, and FAQ across every page.

- Publishing pages where key modules are empty or still contain placeholders.

- Trying to cover multiple intents with one layout (definition + buyer guide + comparison in one page).

- Letting page elements disagree (title promises one thing, headings suggest another, body answers something else).

One small example: a location template for “best plumbers in [city].” If your data feed only has one provider in many cities, half the page becomes “no results” blocks. Even if the URLs are unique, the pages feel unfinished, and hundreds of near-empty pages can drag down trust.

Another issue is template voice drift. You start with careful pages, then add generic intros everywhere to save time. The unique parts shrink, and the repeated parts grow.

A simple guardrail: if a section can’t be filled with real content for at least 70% to 80% of pages, remove it until you have better data.

Quick pre-publish checks (10 minutes per template)

Before you publish a batch, spot-check the template like a real visitor would. Open one page, scroll once, and ask: do I immediately understand what this page is for, and what I can do with it?

The 10-minute pass (do this on 3 random pages)

Run these checks on a few pages from the batch, not just the best example. If 2 out of 3 fail, pause and fix the template.

- First screen: the page answers the main query in plain words.

- One unique section: each page has at least one piece that’s truly specific to that keyword (example, data point, mini FAQ, local detail).

- Titles and descriptions: snippet text is readable, not a keyword pile, and not repeated across pages.

- Helpful elements: if you add an image, table, or example, it teaches something (compares options, shows steps, clarifies a definition).

- “Would I be happy?” test: if you clicked this from search, would you feel satisfied or bounce fast?

Example: you publish 200 comparison pages and pick three at random. If the summary, pros/cons, and recommendation all read the same, add a per-page differentiator (like a “Best for...” section that changes based on verified differences).

A realistic example: scaling without flooding your site

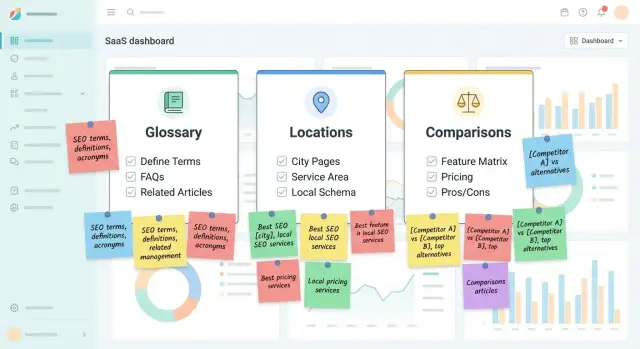

Imagine a SaaS that sells an SEO content API and wants to rank for long-tail searches without publishing thousands of near-empty pages. They choose three template families: a glossary (definition searches), city pages (local intent), and comparisons (buyers choosing between tools).

They draw a hard line between what’s templated and what’s written by hand. The template handles the frame (layout and section order). Humans write only the parts that require judgment: early examples, positioning notes, and “when not to use this” caveats. If a page can’t include at least one real example and one clear recommendation, it doesn’t get published.

Each template type gets its own unique fields so pages don’t read like clones:

- Glossary: definition, plain-language example, common mistake, related terms

- City: target city, top use cases in that city, local proof points you can cite, service coverage rules

- Comparison: who each option fits, meaningful differences, pricing notes (only if verified), decision checklist

Before scaling to 2,000 pages, they publish 20 pages total (a mix of all three types). They track impressions, time on page, and how often people click a next step. Sections that feel repetitive get rewritten once, then reused.

Publishing, indexing, and keeping quality over time

Speed up indexing for batches

Submit fresh URLs with IndexNow and crawler integrations when you publish in batches.

Treat a programmatic launch like a product release, not a content dump. Publish in small batches, pause, then check what real users do. If the first 50 pages get quick exits or no clicks on key sections, improving the template will help more than pushing the next 5,000.

For discovery, make it easy for search engines to find new pages, but only after the template is solid. Submitting fresh URLs can help when you publish in batches.

Watch behavior by template type, not just total traffic. A glossary page and a location page serve different intent, so compare them separately.

Signals that usually tell the truth quickly:

- engaged reads (time on page, scroll depth, clicks on primary sections)

- quick exits (very short sessions)

- impressions vs clicks (title and snippet match the query)

- internal navigation (do people move to the next helpful page)

- feedback themes (what users still ask)

As you learn, update the template, not just one page. Add the section users keep looking for (for example, “pricing factors” on comparison pages), then regenerate the pages that need it.

Be willing to prune. Pages that never become useful should be merged into a stronger hub page or removed so the site stays clean over time.

Next steps: build one good template, then scale carefully

Start small. Pick one page type (glossary, location, or comparison) and a tight set of long-tail queries with clear intent. Prove the template is helpful before you publish hundreds of pages.

If you sell a service, don’t launch 500 location pages in week one. Launch 10 for places you actually serve and where people already search for you. Watch what users do, what they click, and what questions remain.

Put your quality checklist into the workflow as a gate: a page doesn’t ship if it fails the checks. Then automate only after you see real signs of usefulness (engaged reads, clicks to the next step, fewer quick exits).

A practical scaling plan:

- Launch 1 template with 20 to 50 pages that share clear intent

- Add data fields that create real differences (not just swapped keywords)

- Do a checklist-driven review pass before publishing

- Automate after results look good for 2 to 4 weeks

- Expand to the next template type only after fixing what users struggle with

If you’re building this as a pipeline, a tool like GENERATED (generated.app) can help generate and serve content through an API, including polishing and translations, while you keep strict rules about required data and optional sections.

Schedule a monthly review. Improve templates first (weak intros, repeated FAQs, missing sections, outdated data) and only then add more pages. More pages don’t win. Better pages do.

FAQ

What exactly counts as “thin content” in programmatic SEO?

Thin content is when pages look unique (different keywords, titles, or URLs) but provide basically the same answer. It usually happens when your template reuses the same paragraphs and your data doesn’t add real page-specific facts, examples, or constraints.

How do I know if a template has enough unique info to publish at scale?

A good baseline is: you can supply at least 3–5 facts that genuinely change per page, plus one clear primary answer that would be different if the keyword changed. If the only thing that changes is the keyword (like a city name), your template isn’t ready to scale.

Which long-tail keywords work best for templated pages?

Start with queries where intent is obvious and repeatable, like definitions, “in [city]” services, pricing questions, and direct comparisons. Avoid keywords where you can’t reliably add unique details, because the template will produce near-identical pages.

Should I group keywords by intent or by wording?

Group by what the person is trying to do, not by shared words. If someone wants a definition, the page should teach quickly; if they want a local provider, it should remove location doubts; if they want “vs,” it should help them choose.

When should I use a glossary page vs a location page vs a comparison page?

Use glossary pages for clarity, location pages for local options, and comparison pages for decisions. If answering the query requires fresh research and judgment every time, it’s usually better as a normal article, not a template.

What’s the simplest way to plan one programmatic SEO template?

Write the page goal in one sentence (what the visitor should be able to do quickly), then define the fields that must vary per page to make that possible. Build sections as required or optional, and set a hard rule that pages don’t publish when required fields are missing.

What should I do when some pages don’t have enough data to fill the template?

Hide optional sections when data is missing instead of filling space with generic text. If a missing field affects trust (like prices, rankings, or “best” claims), block publishing until it’s verified or remove that claim from the template entirely.

What are the biggest mistakes that create duplicate or low-value pages?

Check whether removing the keyword (city/term/tool name) makes the page read the same; if yes, it’s too generic. Also watch for repeated intros, identical FAQs across many pages, and pages where key modules are empty or feel like placeholders.

What’s a quick pre-publish quality check I can do in 10 minutes?

Open three random pages from the batch and see if the first screen answers the query plainly, then confirm each page has at least one truly specific section (a data point, example, local detail, or scenario-based recommendation). If two out of three feel generic, fix the template before publishing more.

How do I keep quality high when generating pages through an API?

Treat data like part of the product: define a source for each field, format rules, and who owns updates. If you generate pages via an API, tools like GENERATED can help generate, polish, translate, and serve pages consistently, but you still need strict “required fields” rules so automation doesn’t publish empty or misleading pages.