Sep 19, 2025·8 min read

Prevent thin content in templated pages: rules and examples

Learn how to prevent thin content in templated pages with practical minimum content requirements, uniqueness rules, and template upgrades that add real value.

What thin content looks like on templated pages

Thin content is a page that can be crawled and looks “complete,” but gives people little reason to stay. It usually repeats what’s already on other pages, answers the question halfway, or adds no helpful detail beyond a headline and a few boilerplate lines.

Templated pages are higher risk because they’re designed to scale. If the template only swaps a city name, a product name, or a category label, you can publish hundreds of pages that feel different to a machine but identical to a person. Search engines often treat that as low-value duplication, especially when the pages target similar queries.

A quick way to spot the problem is to read three pages in a row. If you can predict the next sentence each time, users can too. The page might not be “wrong,” but it’s forgettable, and forgettable pages rarely earn clicks, shares, or links.

Common signs a templated page is thin:

- The main text is generic filler (definitions, marketing lines, “we offer quality service”) with one swapped token.

- The page answers “what is this?” but not “which option should I choose?” or “what should I do next?”

- FAQs, reviews, pros/cons, or pricing sections are empty or copy-pasted across pages.

- The page has headings, but little original detail under them.

- People bounce quickly because there’s nothing new to read.

Thin content becomes a sitewide quality problem when it’s the majority of what you publish. A handful of weak pages usually won’t sink a site. Thousands of near-identical pages can, because they compete with each other, waste crawl time, and make it harder for strong pages to stand out.

Example: a directory creates 500 “Service in City” pages. Each one has the same three sentences, the same stock FAQ, and no local specifics. Even if each page is technically unique, the experience isn’t. The goal is simple: make each page useful on its own, not just different in its labels.

What makes a templated page valuable (not just longer)

A templated page is valuable when it helps someone do something specific. Length is a side effect, not the goal. The best starting point is intent: does each page clearly answer one real question a person would actually search?

Intent match: one page, one clear job

A good template makes the page’s purpose obvious in the first screen. A “service in city” page should help someone decide: do you serve this area, what’s included, how much does it cost, and what happens next? If the page only swaps the city name while keeping the same vague promises, it feels empty even at 800 words.

A simple test: could someone take the next step without leaving the page? That might be requesting a quote, choosing a plan, comparing options, or learning the exact requirements.

Unique information: real differences, not just tokens

Uniqueness isn’t repeating “{City} + {Service}” in headings. It’s content that legitimately changes from page to page because the facts change: availability windows, lead times, local regulations, typical needs in that area, pricing ranges, or which features matter most for this category.

Practical ways to add real uniqueness without writing every page by hand:

- Add a short “What’s different here” block driven by data (hours, coverage, turnaround times, seasonality).

- Include 2-3 FAQs that are specific to the page type, not site-wide generic questions.

- Show a small comparison table that changes (plans that apply, inclusions, limits).

- Provide a short scenario with numbers (timeline, cost range, steps) that fits the page.

Trust signals matter too. Explain where key claims come from: how prices are estimated, when data was updated, and what could change the outcome.

Make engagement easy. If a reader can understand, compare, and decide with clear next actions and fewer doubts, the page will feel useful even if it’s short.

Minimum content requirements that actually work

Stop thinking in terms of a universal word minimum. Think in terms of what a visitor must be able to do on that page without bouncing back to search.

Write a minimum content spec for each template type. A category page needs different “must-haves” than a location page, product page, or comparison page. Treat the spec like acceptance criteria: if the page can’t meet it with real data, it doesn’t ship.

Build a minimum spec around user tasks

A good spec answers two things: what questions should this page solve, and what decision should it help someone make?

Keep it simple with a short checklist per template:

- 5 to 8 required unique fields (not optional) pulled from your database

- 2 pieces of page-specific guidance text (policy, process, or constraints) tied to those fields

- 1 proof element (review snippet, case metric, certification, or “last updated” with real freshness)

- 1 conversion helper (FAQ, next-step suggestion, or “who this is for”)

- 1 internal sanity check: “Would this page still be useful if the hero paragraph was removed?”

Required unique fields (and when not to publish)

Uniqueness usually comes from structured facts. “Required” means the page can’t render without them. If your location template needs service radius, lead time, and local contact details, those fields must exist or the page stays unpublished.

Set thresholds that relate to tasks, not length. “At least 3 differentiators between A and B” is a better rule than “at least 300 words.”

Add a “do not publish” rule. If a page only has a name and a generic paragraph, keep it in draft. Tools like generated.app can help enforce template specs during generation, but the rule itself should be yours: no real data, no page.

Uniqueness rules you can apply to every template

Aim for pages that feel like they were made for one specific visitor intent, not copied for a keyword. Uniqueness isn’t rewriting the same paragraph 500 ways. It’s adding page-specific facts that change a decision.

Start with a clear purpose statement at the top (1-2 sentences). It should reflect the page’s data, not a generic promise. Example: “Compare same-day boiler repair options in Austin, including typical response times and what affects the final quote.” If you remove the city and it still reads fine, it’s probably too generic.

Rules that work across most templates:

- Include one unique paragraph that cites at least 2 page-specific facts (numbers, constraints, availability, timelines, policies, or local conditions).

- Add one “specifics” section that must differ (pricing range, common use case, required steps, or what to prepare).

- Use FAQs based on real questions for this page type, answered with details that match the page data.

- Add a small set of internal facts that vary per page (turnaround, minimum order, coverage area, supported formats).

- If visuals make sense, include at least one unique visual or a caption that references the page’s specifics.

Concrete example: a template for “Carpet cleaning in [City]” stays thin if it only swaps the city name. Make it unique with something like: “In [City], most jobs fall between $120 and $240 because apartments are often smaller, but pet odor treatments can add $30 to $60. Weekend slots fill up fastest, so booking 3 to 5 days ahead is common.”

If you generate pages at scale (for example via an API such as generated.app), make these rules part of content QA so thin pages can’t slip through when data is missing.

Ways to enrich templates with real value (practical patterns)

Make CTAs match intent

Create adaptive CTAs per page type and track what actually drives next steps.

Focus on blocks that change because the page has different inputs, not because you rewrote the same paragraph 1,000 times. A visitor should learn something specific to this page in the first 10 seconds.

Start with a short summary that uses real signals. Instead of “This page lists X,” write 2 to 3 sentences that reflect the page’s data: price range, availability, rating spread, key constraint, or “best for” use case. If something is missing, say so plainly and offer the next best hint (for example: “No verified pricing found, so sort by reviews and response time”).

Practical patterns that add page-specific value

Comparisons work because they force specificity. Add a small “Top alternatives” or “Nearby options” block based on real attributes like feature overlap or distance, then list 2 to 3 pros and cons tied to the same inputs.

Context is another quick win. A short “Who this helps” block makes the page feel written for someone. Keep it concrete: “Good for teams that need X weekly,” or “Best when you care more about Y than Z.”

A decision guide turns static listings into advice. Keep it short and tied to the page’s values:

- If the main option is above the page’s median price, start with “value picks.”

- If reviews are sparse, prioritize verified providers or items with recent updates.

- If time matters, sort by response time or nearest availability.

- If features vary a lot, pick 2 must-haves and ignore the rest.

Examples, calculations, and small tables also help. Even a simple computed estimate (total cost, time saved, “cost per unit”) makes a template feel earned.

Here’s a small example table for a programmatic pricing page:

| Option | Monthly price | Setup fee | First-month total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic | $19 | $0 | $19 |

| Pro | $49 | $99 | $148 |

If you generate pages via an API (for example, with GENERATED), these blocks are easier to keep consistent: the template stays stable while summaries, comparisons, and calculations update from the same inputs and can be tracked against performance.

Step-by-step: turn a thin template into a strong page

Treat each template like a product page. It needs a clear user job, specific information, and a reason to exist beyond being indexed.

Start by naming your template types and the job each one serves. “Location pages” might help people find services near them. “Feature pages” might help someone decide between options. If you can’t finish the sentence “This page helps the visitor…,” the template is probably only there for search engines.

A workflow that holds up before you scale to hundreds or thousands of pages:

- Write down your template types and the user job for each (one job per template).

- Inventory the data you already have that can be unique per page: prices, availability, specs, opening hours, reviews, FAQs from support tickets, delivery zones, comparisons, policies, examples, outcomes.

- Design 3 to 5 content modules that use that data (for example: “Top picks in this category,” “Common questions for this location,” “How pricing works here,” “What to expect”).

- Add rules for when modules show or hide. If a page has no reviews, hide the review block and show a “What customers ask” FAQ instead. If you don’t have local specifics, don’t pretend you do.

- Create one great example page and use it as the benchmark. Mark what feels helpful, then make the template meet that standard.

Example: a city page that only says “We serve Austin” is thin. If your data can power a short “Services available in Austin,” typical turnaround times, a small FAQ based on real questions, and a clear next step, the same page becomes useful.

Common mistakes that keep pages thin

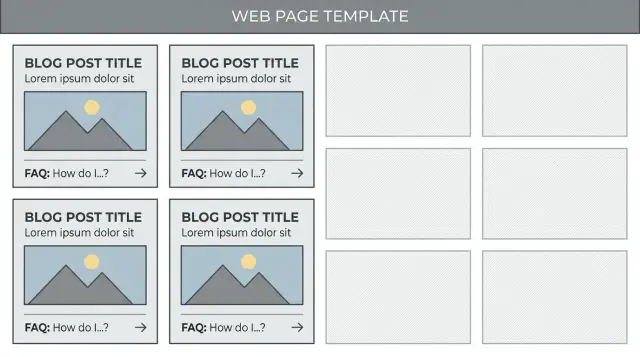

Add page-relevant visuals

Generate and resize images that match each page topic to support SEO and engagement.

The fastest way to end up with thin pages is treating a template like a magic trick: swap a few variables and assume it’s now “unique.” Readers and search engines usually see through that.

A lot of thin pages aren’t “empty” on paper. They have text, headings, even FAQs. The problem is that they add almost nothing that’s specific, useful, or trustworthy.

Common patterns:

- “Unique” fields are filled, but not meaningful (placeholders, defaults, “N/A,” or blurbs pasted everywhere).

- You publish thousands of combinations just because you can, even when nobody searches for them.

- The same intro, FAQs, and closing paragraphs appear on every page, with only the city or product name swapped.

- You rely on synonyms and word shuffling (“best,” “top,” “great”) instead of adding new facts or guidance.

- You ignore pages with no clicks or very short visits for months, so weak pages quietly pile up.

Example: a “Plumber in Oakview” page that says “We offer reliable plumbing services in Oakview” plus the same five FAQs used on 5,000 other towns is still thin. It doesn’t answer what people actually want: typical prices, response time, which neighborhoods are covered, what jobs are common there, and how to choose a provider.

What to do instead when you spot them

Tighten your publish rules. If a page can’t meet your minimum content requirements without filler, it shouldn’t ship.

A practical “value threshold” looks like:

- 2 to 3 data-backed, page-specific details (pricing ranges, availability, specs, constraints, or real examples)

- at least 1 section that changes based on real inputs (not just the title)

- a retire-or-merge plan for pages with no demand or no engagement after a set time

If you’re generating pages at scale, add QA checks to the pipeline (flag pages where unique fields are too short, duplicated across many pages, or missing entirely). Tools like GENERATED can help automate content QA and track performance, but the key rule is simple: don’t publish pages that can’t say something real.

Example: upgrading a location-based template

A common thin setup is a city directory where every page is the same except for the city name: one generic intro, one generic services list, and a contact form. Users land, skim, and leave because nothing answers the real question: “What’s different for me in this place?” Search engines see the pattern too.

Here’s a simple way to upgrade a “Plumbers in {City}” directory (the same approach works for dentists, movers, tutors, and more).

What to add so each city page is truly different

Add details that naturally vary by location. Keep it short, but make it specific.

- Local pricing range (with context): Instead of “Affordable rates,” use something like “Typical emergency call-out: $120-$220 in {City},” plus one sentence about what drives the range.

- Service area notes: Name the neighborhoods or suburbs you actually serve and note any boundaries.

- Lead times: Add a small “Availability” block with realistic expectations, updated from real booking data.

Then add one local paragraph that can’t be swapped between cities. Even a single sentence helps: “In {City}, older homes in {Neighborhood} often need valve replacements during winter freeze-thaw weeks.”

Add a mini case example and city-specific FAQs

A short scenario makes the page useful without making it long:

“Last week a customer in {City} noticed low water pressure in a 1980s townhouse. The fix was a clogged aerator and a partially closed shutoff valve. Total visit time: 45 minutes. Cost range: $130-$160.”

For FAQs, avoid generic ones that appear everywhere. Pull questions from support tickets or sales calls and tie them to the city:

- “Do you charge for parking in downtown {City}?”

- “Can you visit {Suburb} after 6 pm?”

- “What’s the usual wait time on weekends in {City}?”

If you generate pages at scale (for example, with a tool like GENERATED), make sure inputs come from real sources like booking history, quotes, call logs, or verified partner coverage. Generated text should explain real differences, not invent them.

Be honest about coverage. If a city page has no unique data, no demand, and no service capacity, it’s often better to merge it into a broader regional page or keep it out of indexing until you can add real value.

Quick checklist before you publish templated pages

Improve indexing speed

Push new and updated pages to indexing faster with built-in IndexNow support.

Before you publish at scale, review a small sample (10 to 20 pages) from different segments. If you can’t confidently sign off on those, publishing thousands will only multiply the problem.

Use this as a pass/fail gate. If a page fails an item, fix the template (not the page) and re-check.

- Purpose and reader match: Can you explain, in one sentence, who this page is for and what it helps them do?

- Unique data is real (not placeholders): Scan for “N/A,” repeated blurbs, empty reviews, generic descriptions, or the same stats across many pages.

- A hard-to-copy block exists: Include at least one section driven by your own data or selection logic (ranked comparison, expert note, local constraints, calculated pricing ranges, or recent trends).

- FAQs and examples feel specific: Each answer should mention at least one page-specific fact (numbers, options, limitations, or a real scenario).

- Keyword removal test: Delete the main keyword from the title and first paragraph. Is the page still clear and useful? If meaning collapses, it’s written for the phrase, not the person.

A quick practical move: open two pages from different locations or categories side-by-side. If 80% reads the same, you need more variable sections or better rules for when to show them.

If you generate pages via an API (like GENERATED), bake these checks into your QA step so pages that don’t meet the gate never get published.

Next steps: improve one template, then scale safely

Pick one template to fix first, not all of them. Choose the one that already gets traffic (or is closest to ranking). Small improvements there usually show results faster.

Treat the first upgrade like a reference build. Add 2 to 3 strong modules that are genuinely page-specific, then lock those rules in. For example: a category template might get a short human summary, a “how to choose” block tailored to that category, and a small set of unique FAQs pulled from real questions.

Put a simple QA gate in front of publishing

Thin pages ship because nobody checks the output the way a reader would. Add a quick review step for every new template and every template change:

- Does the page say something specific, or could it describe 1,000 other pages?

- Are key sections filled with real data (prices, availability, policies, specs) where possible?

- Are headings and snippets unique, not just swapped keywords?

- Is there a clear next action that matches the page intent?

- Is the page still useful if you remove the hero text?

Track results by template type, not just by URL. Group pages into “location pages,” “product pages,” “glossary pages,” and so on. If one group has low impressions or poor engagement, inspect the shared modules and fix the cause once.

Build a repeatable content workflow

Scaling works when your pipeline reliably produces unique blocks, not just longer intros. A practical mix is: one or two data-powered modules, one plain-language module, and one trust module (reviews, sources, methodology, or clear policies).

If you need help producing and testing these blocks at scale, GENERATED (generated.app) is built for generating SEO-focused content and tracking how modules and CTAs perform by template type. Use it as support for your process, not as a substitute for real inputs and strict publish rules.

A good starting plan: upgrade one template, publish 20 to 50 pages, measure for two weeks, then expand to the next template with the same QA gate and tracking rules.

FAQ

How do I know if my templated pages are “thin content”?

Thin content is a page that looks complete but doesn’t help the visitor make a decision or take a next step. On templated pages it often shows up as the same generic paragraph repeated with only a city, product, or category swapped. If reading three similar pages feels predictable, it’s usually thin.

Is thin content just a word count problem?

No. A higher word count can still be thin if it’s mostly filler, recycled FAQs, or vague marketing lines. Aim for pages that answer the visitor’s real question with page-specific facts, guidance, and a clear next action.

What should be in a minimum content spec for a template?

Make the “minimum spec” about what a user needs to do on that page without going back to search. Require a small set of unique fields your database can provide, add a couple of short guidance paragraphs tied to those fields, include one trust element like freshness or how numbers are estimated, and make the next step obvious.

What counts as “required unique fields” for a template?

Any structured fact that changes the decision is a good candidate, such as price ranges, availability windows, lead times, coverage areas, limits, or what’s included. The key is that it truly varies between pages and isn’t a default like “N/A” or a placeholder. If your fields don’t change, your pages won’t feel different either.

What should I do when a page doesn’t have enough unique data to be useful?

Don’t publish it. Keep it in draft, merge it into a broader page, or wait until you have real inputs that make it useful. Publishing lots of empty variations creates a sitewide quality problem and wastes crawl attention on pages that can’t satisfy intent.

What’s a quick test to catch thin template output before publishing?

Use the keyword removal test. Take the main keyword out of the title and first paragraph, then read it as a human; if it becomes unclear or generic, it was written for the phrase, not the person. Also compare two pages side-by-side and check whether most sentences are identical.

How can I enrich a template without writing every page by hand?

Add blocks that naturally change based on real inputs, like a short “what’s different here” summary, a pricing or timeline note with context, and FAQs that reflect that page’s constraints. A small scenario with numbers can also work well if it’s based on real patterns you see. The goal is not more text, it’s more decision-helping detail.

What makes a “service in city” page feel genuinely different from other cities?

You should include specifics that vary by location, such as typical price ranges, realistic lead times, neighborhoods served, and any local constraints you can state honestly. Avoid pretending to be local if you don’t have the data; it’s better to say what you can confirm and what affects the outcome. A city page becomes strong when it answers “what changes for me here?”

How do I turn a thin template into a strong page step by step?

Identify the template type, define the single job the page serves, and then design modules that use your data to complete that job. Add rules for showing or hiding modules when data is missing so you don’t display empty sections. Create one benchmark page you’d be proud to rank, then make the template meet that standard consistently.

What should I do with thousands of existing thin pages on my site?

Start by auditing by template group, not one URL at a time, because the cause is usually shared modules. Improve the template, tighten the publish gate, and then either upgrade, merge, or deindex pages that can’t meet the minimum spec. This prevents weak pages from piling up again while you fix what already exists.