Sep 22, 2025·7 min read

Meta titles and descriptions at scale: patterns that stay unique

Learn repeatable formulas for meta titles and descriptions at scale, with guardrails for uniqueness, relevance, and avoiding spam signals.

Why scaling meta tags often turns into repetition

Repetition usually starts with a reasonable move: you write one safe template and apply it everywhere. Once you publish hundreds of pages, that safety turns into sameness. The same adjectives, the same promises, and the same word order show up on pages that are actually about different things.

It also happens when the writing focuses on word tricks instead of the page purpose. Swapping synonyms doesn’t create real uniqueness if you’re still making the same generic claim. People skim past it because it looks like every other result. Search engines often treat it the same way and rewrite the snippet because the text doesn’t add page-specific value.

“Unique” doesn’t mean every character must be different. It means the title and description match the page’s intent and include details that would only be true for that page. At scale, the goal is a consistent structure with meaningful variables.

Meta tags usually become duplicates for a few predictable reasons: one template gets reused across different page types (category, product, location, blog), the only variable is a keyword while the value statement stays identical, descriptions lean on vague superlatives (“best,” “top,” “affordable”) instead of specifics, or key data fields are missing and the system falls back to the same default text.

Reusing small parts is fine when it improves clarity. A short brand suffix, a consistent separator, or a stable format like “Primary topic - key detail | Brand” can repeat. The difference should come from the detail: a model number, a location, a comparison angle, a use case, or a concrete promise the page actually delivers.

If every description ends with “Get instant results,” everything blends together. If one page says “Compare 12 noise-cancelling models under $200,” that’s specific, believable, and hard to duplicate by accident.

Start with page types and search intent, not word tricks

Start by grouping pages that behave the same in search. Repetition often comes from forcing one clever template onto pages that answer different questions.

Map each URL to a page type, then write one set of rules per type. Common types include product pages (someone comparing or ready to buy), category pages (someone browsing options), location pages (someone looking for a nearby provider), articles (someone learning), and support pages (someone trying to fix a problem).

Next, define one main intent per page. A category page usually targets “best running shoes” or “running shoes for flat feet,” not both. A support page targets “reset password” rather than “account settings” in general. When intent is clear, templates stop sounding like keyword swaps.

Then decide what must always be present, in this order: the core term (what it is), the differentiator (why this page is different), and the brand (only if it helps). Two product pages can share the same core term but differ by size, material, price range, or use case. Those are the variables worth showing.

Set character targets so previews stay readable. As a rule of thumb, aim for about 50-60 characters for titles and 140-160 for descriptions. Keep a “mobile-safe” version in mind: shorter titles, and the key detail early so trimmed snippets still make sense.

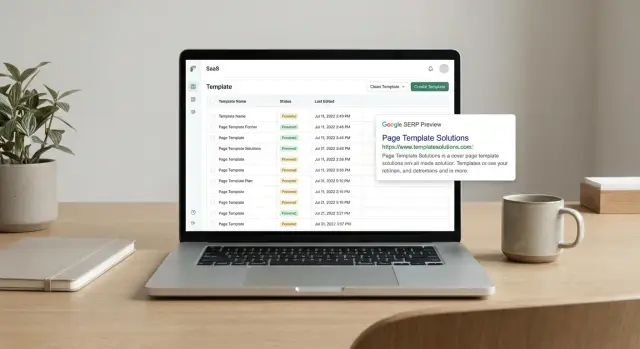

Tools like GENERATED can generate variants per page type through an API, but the quality comes from doing the intent map and “required parts” work first.

Pick the variables that actually make pages different

Uniqueness doesn’t come from synonyms. It comes from the few details that change what the page is actually about.

List the data you already have for each page. Most sites have more than they think: a name, category, location, price, year, size, brand, or a key feature. Choose only 2-4 attributes a searcher would care about before clicking.

A simple test: if you remove this detail, would the page feel like the same result as ten others? If yes, keep it. If it’s filler (an internal ID, a long tag list, or every possible feature), leave it out.

Variables that usually work well include a primary identifier (product name, service, topic), a category or use case (what it’s for), location or coverage area (only when it matters), a price range or starting price (only if accurate and stable), and a year or version (only when it changes the offer).

Set fallback rules because real data is messy. If a variable is missing, the template should still read like a normal sentence. If price is missing, drop the price phrase entirely (don’t replace it with “N/A”). If a location is missing, use a broader region or skip location. If a name is too long, trim it sensibly and keep the category.

These choices keep tags relevant and reduce the risk of spam signals caused by stuffing every attribute into every page.

Meta title patterns that scale without sounding templated

For hundreds of pages, the goal isn’t to be clever. It’s to be specific. Tie every title to one clear thing that changes per page (a location, a model, a category, a use case) and keep the rest consistent.

Pattern 1: Primary term + specific modifier + brand

Use this when each page has a strong “what makes it different” variable.

Example shape: {Primary term} - {Specific modifier} | {Brand}

A good modifier is factual: “for small teams,” “in Austin,” “pricing,” “API,” “templates,” “2026,” “for Shopify.” A weak modifier is vague: “best,” “top,” “ultimate.” If the modifier doesn’t change across pages, it isn’t doing any work.

Pattern 2: Primary term + outcome (what the user gets) + brand

Use this when the intent is “help me do a job,” not “tell me what this is.”

Example shape: {Primary term} - {Outcome} | {Brand}

Outcomes that work: “Generate faster,” “Fix common errors,” “Compare options,” “See examples,” “Learn the steps.” Keep outcomes short so they don’t push the unique variable out of view.

Pattern 3: Primary term + selection cue + brand

This works well for list and comparison pages.

Example shape: {Primary term} - {Selection cue} | {Brand}

Selection cues should match list intent: “Examples,” “Checklist,” “Top picks,” “Best for {audience},” “Alternatives.” Use them only when the page really is a list or comparison.

To keep things consistent across your site, choose one separator style (“-” or “|”), pick a casing style (Title Case or sentence case), and standardize abbreviations (“AI” vs “A.I.”). Set a max length target and enforce it everywhere, so templates don’t turn into accidental truncation tests.

Meta description formulas that stay human

Automate content via API

Serve SEO-ready content through an API and keep outputs consistent across your site.

A good meta description is a small promise. It should tell a searcher what they’ll get on the page, in plain words, without sounding like a template or a keyword dump.

Start with one clear outcome (what the page helps the person do). Then add one proof point or detail using a variable that truly changes per page (a city, a category, a price range, a use case). If you cram in too many variables, it usually turns into a comma chain that reads like spam.

A few formulas that stay readable:

- Do X with Y. Includes [one variable detail] so you can decide faster.

- Learn how to do X for [variable]. Simple steps, examples, and common mistakes to avoid.

- Compare [variable A] vs [variable B] for X. See key differences and pick the right option.

- Get [variable] templates for X. Copy, tweak, and use them today.

A soft call to action can help, but only when it matches intent. For informational pages, “See examples” or “Get the checklist” fits. For transactional pages, “Check pricing” or “View options” can work. If the query is “what is” or “how to,” “Buy now” is usually the wrong tone.

Keep the language tight. Avoid repeating the same keyword twice, avoid long comma lists, and avoid filler superlatives unless the page proves them.

Example: if you have 300 glossary pages, don’t use “Definition, examples, and benefits” on every page. Instead: “Clear definition of [TERM], a plain-English example, and where it’s used in real work.” If you generate these in a tool like GENERATED, set it up to use one variable (the term) plus one specific detail pulled from the page content, not a generic template bank.

Step-by-step workflow to generate and review at scale

A practical workflow

At scale, the goal isn’t to “spin” text. It’s to use a small set of patterns that pull the right facts for each page type, then run checks so near-duplicates don’t slip through.

- Build a template library per page type. Start with 3-5 types (category, product, location, comparison, article). Give each type 2-3 approved title patterns and 2-3 description patterns.

- Define variable priority and fallbacks. Decide what makes the page different (brand, model, location, price, year, primary benefit), then set rules like: “If Model is missing, use Category; if Category is missing, use Brand.”

- Generate 2-3 variants per page. Don’t publish all of them. Store them for later testing or rotation.

- Run de-duplication checks before publishing. Flag tags that are too similar, too short, missing variables, or repeating the same phrases.

- Manually review the pages that matter most. Read tags like a human, not a spreadsheet. Review top traffic pages more often.

Example: for a location page, the title might prioritize service + city, while the description pulls one proof point (reviews, delivery time, or range). If a city name is missing, the fallback shouldn’t become “Best Service | Brand” across 200 pages.

If you generate tags via an API (for example, using GENERATED), keep templates and rules in versioned configs so changes are deliberate and easy to roll back.

Common mistakes that can look like spam

The main risk isn’t that Google “punishes” templates. The risk is that pages look identical to people and to search engines, so snippets get rewritten or ignored.

One common mistake is stuffing the same modifiers everywhere. If every page is “Best,” “Top,” “Cheap,” or “2026,” those words stop meaning anything and start feeling like clickbait. Use modifiers only when they’re true for that page.

Another issue is repeating the exact keyword twice in one title. It reads awkwardly and looks like you’re trying too hard. A cleaner title usually wins: say the main topic once, then add the differentiator (location, category, use case, or audience).

Also watch for titles that are just a pile of attributes. A string like “Blue, Waterproof, 10L, Lightweight, Nylon” is hard to scan. Search results reward clarity, not a spec sheet.

Descriptions feel spammy when they don’t match the page. If the page is pricing, but the description promises a tutorial, users bounce. That mismatch is a trust problem.

Signals to remove from templates:

- ALL CAPS, repeated exclamation points, or gimmicky punctuation

- Forced year stuffing on pages that aren’t time-sensitive

- Claims the page doesn’t actually support

- Keyword repetition that breaks the sentence

- Titles that are just filters, tags, or comma-separated traits

Example: for 300 city pages, avoid “Best Dentist in {City} - Best Dentist {City} 2026!!!”. A safer version is “Dentists in {City}: Hours, Reviews, and Appointments” (mention the year only if the page truly changes by year).

If you generate snippets through a system like GENERATED, add rules that block caps-heavy output and check the description against the page type before publishing.

Uniqueness guardrails and simple QA checks

Scale SEO across languages

Translate and polish content so each locale gets natural, relevant snippets.

The fastest way to lose quality at scale is letting duplicates slip through. A few guardrails let you move quickly without sounding copied.

Guardrails that prevent “same page, same snippet”

Set a similarity threshold. You don’t need perfect uniqueness, but you should catch clusters where too many titles are identical except for a token. A practical rule: if more than 5-10 pages share the exact same title after variables are filled, that page type needs a new pattern.

Watch for empty variables. Missing city, price, or category values create gaps like “Buy in | Brand”. Treat empty variables as errors, not edge cases. Use sensible fallbacks (for example, a broader category name) instead of leaving blanks.

Keep a short blocked-words list that matches your tone and avoids spam signals. Words like “best,” “cheap,” “#1,” or repeated exclamation marks can be fine once, but risky when repeated across hundreds of pages.

Quick QA checks you can run weekly

A lightweight checklist helps before publishing or pushing updates:

- Flag title/H1 mismatches (different topic, not just different wording).

- Find duplicate snippets: the same title and description across many URLs.

- Catch placeholders that leaked (like {city} or %CATEGORY%).

- Spot overlong titles (high truncation risk) and very short descriptions (low context).

- Review the top templates by page count to make sure they still read naturally.

Example: if your template is “{Service} in {City} | {Brand}”, pages missing City shouldn’t publish that pattern. Route them to something like “{Service} near you | {Brand}” so the copy still reads clean.

If you generate via an API (like GENERATED), store QA flags with each page so editors only review pages that fail checks, not everything.

When to refresh meta tags, and when to leave them alone

Changing meta tags everywhere is risky. Treat updates like navigation or pricing: touch what matters most, and do it with a clear reason.

Prioritize pages with the most traffic potential, usually top categories and key locations. Small improvements there beat rewriting 500 pages that barely get impressions.

Good reasons to refresh

Refresh titles and descriptions when something real changed on the page, or when the snippet is clearly out of date. Common triggers include pricing or plan changes, stock or availability changes, features added or removed, years that matter (“2026” pages), or a visible shift in search intent (the ranking pages are now answering a different question).

Example: if you have location pages for “Accounting software in Austin” and you add a new feature like multi-currency invoicing, update the description for your top 10 locations first, then expand if results improve.

What to keep stable

Consistency isn’t the enemy. Keep stable parts stable: your brand format, separators, and a few core phrases that help users recognize you in results. At scale, the goal is controlled variation, not constant rewriting.

Track changes like a design system. Log which template version generated which pages, and keep a quick rollback path if rankings or CTR drop.

Save templates with a version name and date, note the variables used (city, category, product), record where you deployed the change (which page types), re-check performance after 7-14 days, and keep the previous version ready to restore.

If you generate tags programmatically, tools like GENERATED can help keep template versions and outputs organized so you can test updates without losing what was already working.

Example: one template set across hundreds of pages

Set up page type patterns

Create a small template set per page type and produce consistent, non-repetitive snippets.

Imagine a directory site with 500 city pages (one city, many providers) and 200 service pages (one service, many cities). You want meta titles and descriptions at scale, but each page still needs to feel written for that query.

City page template (with one local differentiator)

A title pattern that stays specific:

Title template: {Service} in {City}: {Top Differentiator} | {Brand}

The differentiator should be something the page can prove, like a real count or a concrete feature.

Example title: Plumbers in Austin: 47 Verified Pros | ExampleDirectory

For the description, mirror what the page actually shows, in the same order.

Description template: Compare {Service} in {City}. Browse {ProviderCount} pros, {KeyFilter1} and {KeyFilter2}. See typical pricing from {PriceRange} and response times. Book today.

If your page has sections like “Top-rated,” “Pricing,” and “Availability,” the description should hint at those, not promise things that aren’t there.

Handling missing data without duplicating

Small cities often have gaps. Instead of falling back to one generic line everywhere, use a tiered fallback:

- If

ProviderCountis missing, use{NeighborhoodCount} neighborhoods covered. - If

PriceRangeis missing, useGet quotes from local pros. - If both are missing, pull one unique fact you do have:

{NearestLargeCity} area coverage.

Before vs after (make it specific)

Before (repetitive): Find the best plumbers in Austin. Compare prices and reviews. Call now.

After (specific): Compare plumbers in Austin. Browse 47 pros, filter by 24/7 availability and drain cleaning, and see typical pricing from $120-$350 before you book.

Next steps: a checklist and a practical way to automate

Once the patterns are designed, the work is consistency. Each page should read like it was written for that page, not pulled from a slot machine.

Use this pre-publish check before shipping a batch:

- Does the title match the page’s main intent (buy, compare, learn, local)?

- Is there one clear differentiator (price range, use case, location, size, audience)?

- Could two pages accidentally produce the same title or description?

- Does it read like a normal sentence, not a keyword list?

- Is anything “too good to be true” (all caps, excessive punctuation, vague superlatives)?

Decide what “working” means so you don’t judge changes by vibes. Track a small set of signals per template family (category vs location pages, for example), and give changes a couple of weeks before calling them.

Metrics worth watching include CTR by query group and page type, index coverage (new pages indexed vs excluded), pages that needed manual edits (and why), duplicate title/description reports from your crawler, and brand or compliance issues flagged by reviewers.

Set a monthly routine: pick one template family, review the worst 20 pages and the best 20 pages, then adjust one variable at a time (like the differentiator line or the call to action). Document the winning version so future pages stay consistent.

If you want automation, treat it like a production system: inputs, rules, and QA. GENERATED (generated.app) is one option for generating meta tags via API and tracking performance, but it still works best when you feed it clear page types, approved variables, and QA rules before you publish in batches.

FAQ

Why do my meta titles and descriptions start repeating when I scale to hundreds of pages?

Start by separating pages by type and intent, then give each type its own small set of approved patterns. Keep a consistent structure, but make sure each tag includes 1–2 details that are true only for that page, like a model, city, use case, or count.

How do I choose different templates for product, category, location, and article pages?

Write one set of rules per page type, because different pages answer different search needs. A product page should highlight a decision detail like version, fit, or price range, while a support page should promise a fix and name the exact issue, and an article should promise learning or examples.

What variables actually make meta tags feel unique (without stuffing keywords)?

Pick 2–4 attributes that change what a searcher expects after clicking. Good variables are things people decide with, like model/version, audience or use case, location (when relevant), a stable starting price, or a concrete count such as number of items or providers.

What should I do when key data like city or price is missing?

Set fallback rules that remove the missing part instead of replacing it with placeholders. If price is missing, drop the price phrase; if city is missing, switch to a broader region or a neutral wording that still reads naturally, so you don’t end up publishing the same generic line everywhere.

What length should meta titles and descriptions be for readable search snippets?

Aim for roughly 50–60 characters for titles and 140–160 for descriptions, and put the most important detail early. This helps the snippet still make sense when it’s trimmed on smaller screens or crowded results.

How do I write meta descriptions that sound human instead of templated?

Use one clear promise plus one proof point that matches the page, and keep the sentence natural. A description works best when it tells the user what they can do on the page and adds a specific detail like a comparison angle, a count, a location, or a clearly stated outcome.

What are the biggest meta tag mistakes that can look like spam?

Overused superlatives, repeated keywords, and punctuation tricks are common triggers for “spammy” vibes and snippet rewrites. Another frequent issue is promising something the page doesn’t deliver, like advertising a tutorial on a pricing page, which hurts trust and clicks.

How can I QA meta tags at scale without manually reading every page?

Run similarity checks to catch clusters where too many pages output near-identical text, and treat empty variables as publish-blocking errors. Also watch for overlong titles, very short descriptions, leaked placeholders, and title/H1 topic mismatches so the snippet matches the page’s real intent.

When should I refresh meta tags, and when should I leave them alone?

Refresh when something real changed or when the current snippet is clearly outdated, especially on pages with high traffic potential. Keep stable elements like separators and brand formatting consistent, and version your templates so you can measure impact and roll back if performance drops.

Can I automate meta tag generation through an API without losing quality?

Generate a few variants per page type, store them with the inputs used, and run de-duplication and formatting checks before publishing. Tools like GENERATED can help generate tags through an API and track performance, but the results depend on having clean page types, approved patterns, and strong fallback rules first.